The Importance of Feedback in the Writing Process

- A chapter from How To Write Evocative Poetry -

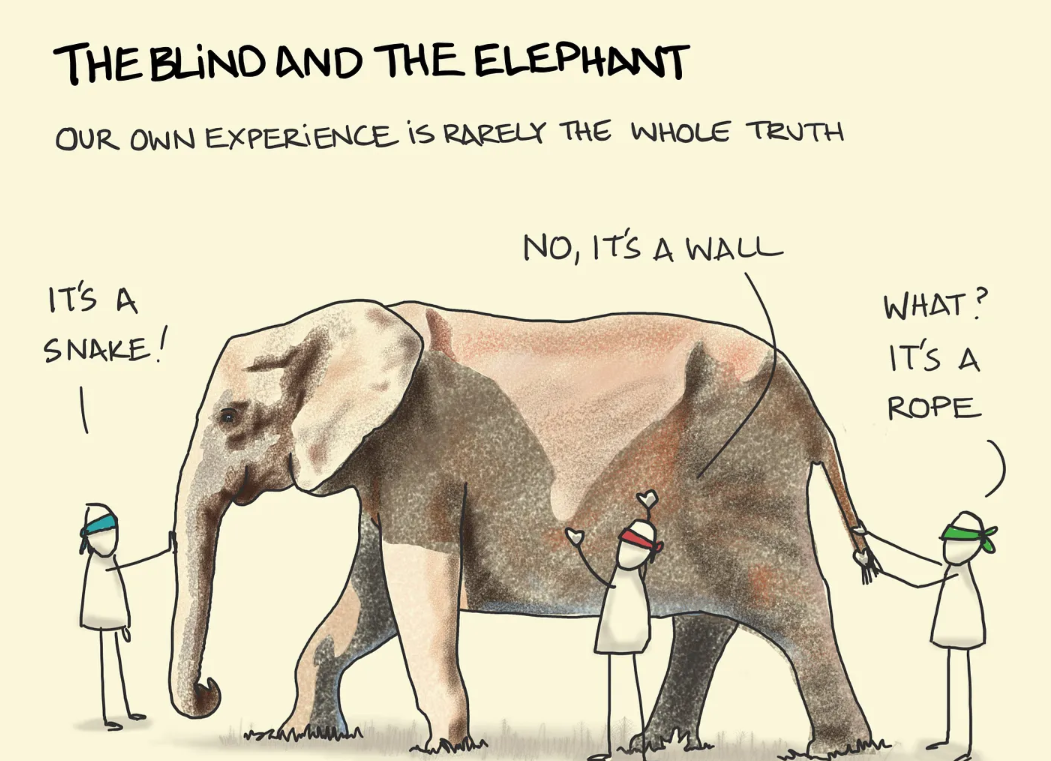

Sometimes we are simply too close to our work to be able to see it for what it is. Perhaps the subject matter is too emotional, or the writing process was too taxing. Maybe our egos are over inflated and are not allowing us to see the flaws. Our self-worth might be down and we are doubting our ability to create anything of value. Or perhaps another set of eyes could solve the problems we cannot even see.

In a previous section I discussed the concept of splitting the creative and editing into different roles to ensure that you get out of your own way and just write. This is vital as you cannot be effectively doing both creation and editing at the same time. Despite this split, and even with a time delay, it can still be hard to detach yourself enough from the process to see your work for what it is. This is where an editor can come in handy. For poetry, I use my wife for this purpose who, for the most part, tweaks some grammar here and there and ticks my poetry off as great. She often is a cheerleader when she sees I need it and highlights potential changes when appropriate. Every now and then however she tells me I can do better, or that a poem isn’t done yet, or that it isn’t good enough. It stings, but I have learnt to trust her. Because she is right.

The most poignant example of this comes from the poem Can’t Quite Express – a mono-rhyming poem I wrote seven years ago. It was a mere 128 words and at the time I felt it aptly expressed what I felt I couldn’t express (the irony of the title was intended). She helped me to whittle down this poem to be lean, cutting, and poignant, and then approved it. However, seven years later, I returned to the poem, extending it to 1261 words, believing that perhaps the poem had evolved into 6 minute spoken word ‘song’. Once again, we went through the editing process, tweaking and fixing it. Nonetheless, the result still didn’t feel quite right, and another 245 words came.

I thought I was done, but she told me it wasn’t. She still felt like there was more - and well, she was right. Over the next few days, Can’t Quite Express became a 6704-word epic poem, that I ended up publishing as a standalone book. Without her prompting, I would never have completed it – or even known of its existence within me. She helped me cut the longer form of poem down by a quarter, highlighting problematic verses, as well as things that didn’t quite fit with the rest of the piece. Acting as my editor, she pulled it out of me, prompting me to do more, highlighting where I could do better, guiding the process, and suggesting areas that weren’t working. The result is far better than I ever could have created on my own.

Can’t Quite Express (original)

There are things I want to say

But just can't quite express

Ruminations and meditations

I'm too afraid to address

Like the veil over my eyes

That keeps me hidden from the stress

To the dark wishes

I'm fighting to suppress

Like the fear and anxiety

That I will constantly transgress

To the past expressions

I am never going to confess

Like how everything I do

Gives me nothing but duress

To the unwavering ache and torment

That’s causing me to regressI must profess

I desire to express my stress

Confess to address this abscess

To obsess on happiness

To aim for excess

And to stop living like a fucked-up messYes

I want to make progress

But there are just some things I can't quite express

I am blessed to live with my chosen editor, but that comes with some potential issues. I have had to train myself in how to best receive feedback and her on how to best give it (tips below). Your editor may be a friend, a family member, an online connection, or paid help. Find someone who you can both work with, and importantly hear negative feedback from whilst maintaining the relationship. I have been writing for years and it is still hard not to take it personally. I know she isn’t criticising me but nonetheless it can still feel like it. Those feelings, whilst valid, have no place in the process. And as such need to be managed. To this end, I have now also started branching out and receiving help from friends and fellow writers, all who provide me with different kinds of advice and feedback, all of which I am extremely grateful for.

Share the following advice with your editor, so they know how to give feedback, and what to expect from you during the process:

Tips on receiving feedback:

When receiving feedback, be quiet and listen. Don’t comment until they have finished expressing their opinion. Don’t defend your work or justify why you made the choices that you made. Just listen.

Once you have heard them out, ask specific questions. What did you think of this part? How did it make you feel? Were there any areas that didn’t work? Why? Did you notice any loose/wasted words. Is it finished?

If you want cheerleading, ask for it. Just know that if you do, you cannot also get constructive criticism at the same time. If needed, tell your editor to give you ‘the shit sandwich’ – praise, critique, praise. This approach makes it easier to manage the emotions that can arise. Alternatively, let them know you need to be told that your effort/intentions are good (cheerleading), but you would like specific help to make your work better.

Remember that it isn’t their job to write or even fix the poem. They are just there to highlight potential issues that you may not be aware of. It is your job to fix the issue.

You, the writer, choose when and how to take the advice of the editor. Ultimately it is your work, and thus your decision as to how the completed piece should look.

Thank them for giving feedback – navigating the emotions of a poet can be hard, and even if you are paying them, they still should be thanked!

Tips on giving feedback:

Don’t give unasked for feedback – even if you have worked with them before. Wait until they ask for your services before you offer your opinion.

Ask if they want critique or cheerleading. Sometimes your writer will just want praise for doing a good job, if so, give it to them. Just make sure that you are clear that the cheerleading isn’t a critique.

Don’t (at least initially) attempt to ‘fix’ the work or offer suggestions. This may make the poet change the piece to suit your ideas, not theirs. They are the writer, not you. A better approach is to share what you felt whilst reading. What parts jumped out at you? What parts emotionally moved you? Bored you? Confused you? Show them how you felt and let them tweak the piece to address those feelings - then repeat until the piece shines.

Only give feedback on things you are competent at/are asked for, eg: if you don’t know how to copy edit, don’t offer to do it!

Remember that the editing process is ongoing and often takes multiple attempts before the poem is at a ‘publishable standard’. Some of the poems within this book were fine upon first writing, others took over ten iterations to get it right. It is important to be patient, both with yourself and your editor. If your editor is telling you that something isn’t working and you cannot figure it out then and there, that is okay. Put the piece down and work on something else for a while. Perhaps with fresh eyes you will be able to fix the problem.

I adhere to the adage that 80% is done. Don’t get me wrong, I want to make my work perfect, but I know the risk of the attempt. Firstly, it is impossible to achieve perfection – by my own or anyone’s standard. Secondly, I know that the attempt will hamper my overall writing career. I could have rewritten the first chapter of my first book again and again. In fact, I could still be doing so. That chapter would have been amazing, and undoubtedly better than it currently is, but if I had done that, I wouldn’t be writing this book, nor would I have learnt the many lessons along the way that my later work gave me.

Summary

Perfection is in the process, not in the final product. Write the poem and then edit the poem – potentially with the help of another person. Then write a new poem. Repeat.

This chapter is from the book How To Write Evocative Poetry